¶ Introduction

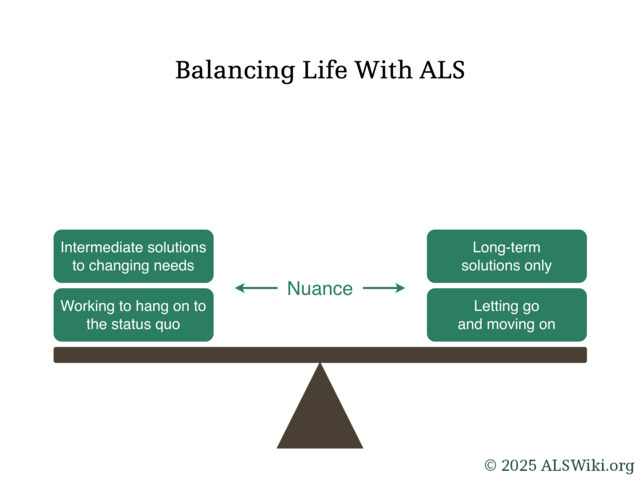

A significant challenge in living with ALS is the need to continuously adapt as the level of disability increases. Other disabilities, such as those caused by a spinal cord injury, usually involve making a fixed number of major adaptations over a short period of time, and then embracing the "new normal".

¶ Rate of Disease Progression

¶ Definition

There are no formally defined criteria for what constitutes "fast", "moderate", or "slow" disease progression. Still, some reasonable generalizations can be made.

Fast progression is suggestive of a rate whereby significant loss of function is observed and many interventions are needed in a short period of time. For example, a patient may be given a ventilator when there is little noticeable difficulty breathing, and not long thereafter, become heavily dependent upon it.

Slow progression is suggestive of a rate whereby loss of function is minimal across a relatively long period of time, such as a few months. For example, someone may have minor difficulty walking early in the year, but is still able to climb up and down stairs much later in the year.

Moderate progression is progression that is not reasonable to describe as being fast or slow.

An ALS patient may experience a change in rate of disease progression over the course of the disease. It may speed up or slow down, sometimes quite significantly.

¶ Implications

The rate of disease progression can have a significant effect on lifestyle and decision-making.

¶ Fast progression

A person with fast disease progression would benefit from reducing the number of adaptations, and skipping intermediate solutions as they may only be useful for a short time. Examples include:

- avoiding specialized adaptive equipment to help get in and out of a regular car seat; such equipment is expensive and rarely covered by government or private insurance

- avoiding home renovations, as they may not be completed in time to make use of them

- avoiding installing a stair lift, as getting on and off of the lift may soon become impossible

With fast disease progression, it is even more important to get ahead of essential tasks, such as estate planning and adapting for late stages of the disease, including establishing and maintaining access to reliable healthcare.

¶ Slow progression

A person with slow disease progression may be able to maintain a higher quality of life by using adaptive equipment and other resources that allow them to remain closer to a normal life. Examples include:

- buying a recumbent bicycle that they are able to ride despite minor weakness in the legs

- working with an occupational therapist to get adaptive driving equipment so that they can still drive their car independently

- installing a stair lift, so they can access all parts of their home for longer

With slow disease progression, it is still important to prepare for advanced stages of the disease, as the rate of disease progression could accelerate at some point in the future. Further, over long periods of time, important tasks could be forgotten and left incomplete.

¶ Planning Ahead

Planning ahead is essential with ALS. Acquiring necessary adaptive equipment (and in some cases, the skills to use them) takes time. It is far better to receive a needed piece of equipment too early, than too late.

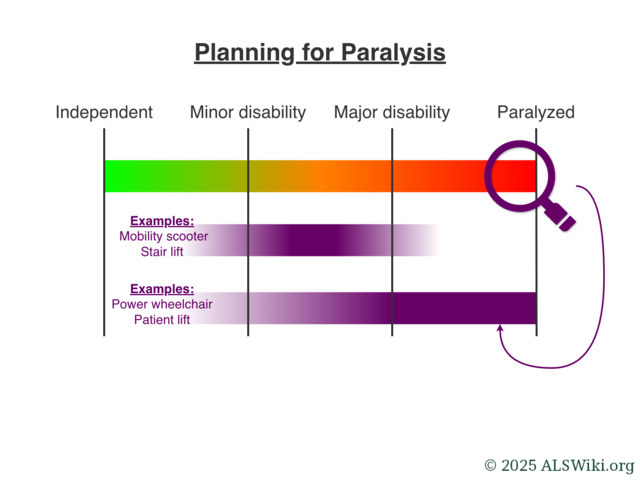

Planning for paralysis is a frequently used term in the ALS community; it refers to making larger decisions which are compatible with later stages of ALS when needs will be at their highest.

Some patients may end up needing to move to a different home in order to have suitable living arrangements. Since moving is a large undertaking, it makes sense to do it only once. As such, the new home should be suited to the later stages of living with ALS, as opposed to present-day needs, or what is perceived to be just around the corner. Otherwise, the patient may need to move again, and it could be at a point in their disease progression where doing so would be stressful and difficult.

It can be possible to reduce the number of adaptations for intermediate stages of disability, by skipping ahead to more versatile equipment and techniques. Doing so can save money and mental burden, as there would be fewer adaptations to make and less equipment to buy. This principle is in line with the concept of planning for paralysis.

Example: Toileting

Using toileting as an example, consider the following stages of adaptation:

- Use of a toilet seat riser to help stand up from the toilet more easily.

- Use of an over-the-toilet commode chair with handles so that the patient can use their arms to help stand up, providing even more assistance than the toilet seat riser.

- Use of a wheeled commode chair so that it's possible to be pushed to the toilet by an assistant.

In this case, the wheeled commode chair, which will be needed eventually, can actually be used to cover all of these stages. Most models come with adjustable arms, and an adjustable height to suit the needs of the patient.

Counter-example: Eating

Eating is a significant part of the human experience, and is a fundamental component of culture. Since the risk of injury is minimal, it often makes sense to continue eating independently, using any reasonable adaptation, until it is no longer feasible. Such adaptations may be as follows:

- Using special cutlery or a universal cuff

- Adapting one's diet to foods that are easier to cut or chew

- Using a robotic feeding machine

Since independent eating has a strong connection to dignity for most people, investment in this area may be worthwhile. More expensive equipment, such as a robotic feeding machine may be rented since it is known it will likely not be used long-term.

¶ Maintaining Dignity

Independence is fundamentally linked to a sense of dignity. Most people prefer to carry out daily tasks such as eating, bathing, and toileting without assistance.

One way to preserve dignity while coping with the loss of independence is to make the decision to accept help on one's own terms and timing. Choosing to seek assistance proactively can provide a sense of control, rather than waiting until a sudden decline forces a reactive adjustment.

¶ Balancing Independence with Safety

Part of adjusting to changing levels of ability involves making adaptations that may carry some degree of risk. While it is fully within the patient’s right to take such risks, it remains important to be realistic about their capabilities in order to prevent injury or other problems.

Tasks that have become difficult to perform independently should be discontinued before they lead to an accident or injury, especially if significant adaptations have already been made.

Testimonial: Stuck in Bed

I was gradually having a harder and harder time standing up and out of my bed. We had put the bed on top of deck blocks to help raise it, to make it easier for me to stand. This worked for a few months and didn't cost much money to do.

However, as time progressed, I was having greater and greater difficulty standing up from the bed. The mattress was soft, so when I pushed my hands down into it to help stand, I wouldn't get much force out of it.

One morning, seemingly out of nowhere, I could not summon the strength to stand up from the bed. I was stuck there, sitting up at the side of the bed, waiting for someone to come home so I could ask for help.

Fortunately, someone came by only a few minutes later. If it weren't for that, I would've spent all day there.

– Craig R, diagnosed with ALS at age 38

¶ Controlling Costs

Living with ALS often brings with it significant financial expense, including major purchases, and recurring expenses.

Some of the largest major purchases include:

- a new home, or major renovations

- wheelchair van

- power wheelchair

- bedding, including frames and special mattresses

- patient lift and slings

Some of the most costly recurring expenses include:

- wages for a live-in caregiver, or home care assistants

- monthly fees for living in a care facility

- taxis and other forms of transit

- supplies such as ventilator masks, briefs, gloves, and so forth

Costs can be reduced by using the following principles:

Apply for all government or private financial assistance programs that are available. These programs exist to help people who need them. Financial assistance with caregiving is of great benefit, as are programs that subsidize adaptive equipment.

Avoid making major purchases that do not have long-term utility, or cannot be sold to recover much of the initial expense. For example, renovating a rural home may give poor return on investment if adequate care is unavailable and relocation is inevitable.

Skip adaptive equipment purchases associated with intermediate stages of the disease, when it is known that they will eventually need to be replaced with more capable equipment.

Make a realistic assessment of transportation needs; wheelchair vans are expensive and should be avoided unless it is clear that it would get used frequently, and that someone is available to drive it.

¶ See Also

- Acquiring Adaptive Equipment Sourcing and financing equipment

- Stay-or-Move Decision Factors in deciding whether to stay or move

Newly Diagnosed with ALS

Article Collection

- First Steps After Diagnosis

- Adapting to Disease Progression

- Medical Decisions

- Home Assessment

- Acquiring Adaptive Equipment